The Quest for Javascript CPS: Part 2

tl;dr: I successfuly compiled a Lisp to Javascript in Continuation Passing Style (CPS) with an acceptable performance hit, and was able to write a stepping debugger and a solution for callback hell

Recently I posted some initial research I was doing in transforming Outlet, a Lisp, into Continuation Passing Style (CPS) form before compiling it to Javascript. To recap, CPS requires that every statement takes a continuation (a function in my case) and sends the result to it. I was very worried about the performance of adding tons of anonymous functions and function calls.

The post includes early benchmarks which confirmed my suspicions, or so I thought. The performance was orders of magnitude slower, and I ended the post with a plea for suggestions on getting performance bearable. Chris Frisz has been working on a similar project for Clojure, and had some great suggestions and others were skeptical that this could work without a huge amount work.

After toiling away last week, racking my brain and scouring research papers for solutions, I'm happy to announce that it works, and I can show you right now!

First, Why I'm Doing This

I think a lot of people were confused on what I am trying to achieve with CPS. jules on HN is exactly right in that the techniques and performance hit you can endure depend on what you're trying to do with it.

My goal with CPS is to allow in-browser stepping debugging. The user should be allowed to pause the program at any time and step through code. CPS allows me to control the stack completely independent of the hosting environment, so the non-blocking nature of the browser is not a problem. Outlet will not support call/cc or explicit continuations (not sure about TCO yet). CPS is basically "debug mode".

Other common uses of CPS include language support for explicit continuations (call/cc) and using it as an intermediate language in a compiler (as described in Appel's Compiling with Continuations and more recently Kennedy's Compiling with Continuations, Continued.) This is all very interesting stuff, and it remains to be seen how much CPS will infect Outlet.

For now, using it as just a "debug mode" dramatically affects how I implement CPS. For example, I can't implement certain CPS optimizations like continuation reduction because I need to step through every statement. However, I can suffer a decent performance penalty because it's just for debugging (but not too much).

The Search For Optimized Continuations

After the last post, I set out to optimize the generated CPS. I grabbed several research papers, my sketchbook, a pencil, and sat down at a coffee shop. There must be a way to get this to work, I thought. I could feel it in my gut.

According to profiling, the primary bottleneck was allocation of continuations (all the anonymous functions). However, I can't sacrifice many of them because I need them for the stepping debugger. Nothing in the research papers stood out to me as a clear solution to this problem (admittedly, I only skimmed a few, but I'm wary of keeping my nose in papers for too long).

I had an idea that started with this premise: numerous function allocations is more costly than explicit environments. My idea can be explained in 3 steps:

- Use explicit environments instead of relying on Javascript scoping/closures

- Hoist every single function to the top-level as a static named function

- Push and pop continuations on/off a stack for function calls

The benefit is that all functions are allocated only once when the program loads, but the cost is that referencing and setting variables is slower. Could this possibly work?

If you don't mind reading ugly code, the implementation is here. I also wrote functions to manage environments in a way that should be fast (pre-allocates space, etc). The continuation stack is implemented at the bottom of that file.

Let's take a look at what this new CPS form looks like. Say we have the following program:

(define (foo x)

(if (> x 0)

(+ 1 (foo (- x 1)))

x))

(foo 20)

It now generates the following program:

(cps2-trampoline

(begin

(define

o10

(lambda

(x)

(extend_environment

(quote o3)

(quote initial)

(quote [x])

arguments)

(if

(>

(lookup_variable

(quote o3)

(quote x))

0)

(begin

(push_continuation o9)

(cps2-jump

(lookup_variable

(quote o3)

(quote foo))

[(-

(lookup_variable

(quote o3)

(quote x))

1)]))

((pop_continuation)

(lookup_variable

(quote o3)

(quote x))))))

(define

o9

(lambda

(o5)

((pop_continuation) (+ 1 o5))))

(define

o8

(lambda

(o1)

(begin

(push_continuation o7)

(cps2-jump

(lookup_variable

(quote initial)

(quote foo))

[20]))))

(define

o7

(lambda

(o6)

((lambda

()

(pp

(str

"halted with result: "

o6))

#f))))

(o8

(define_variable

(quote initial)

(quote foo)

o10))))

You can probably read it better as Javascript:

cps2_dash_trampoline(((function() {

var o10 = (function(x) {

extend_environment("\uFDD1o3", "\uFDD1initial", vector("\uFDD1x"), arguments);

return (function() {

if ((lookup_variable("\uFDD1o3", "\uFDD1x") > 0)) {

push_continuation(o9);

return cps2_dash_jump(lookup_variable("\uFDD1o3", "\uFDD1foo"), vector((lookup_variable("\uFDD1o3", "\uFDD1x") - 1)));

} else {

return pop_continuation()(lookup_variable("\uFDD1o3", "\uFDD1x"));

}

})();

});

var o9 = (function(o5) {

return pop_continuation()((1 + o5));

});

var o8 = (function(o1) {

push_continuation(o7);

return cps2_dash_jump(lookup_variable("\uFDD1initial", "\uFDD1foo"), vector(20));

});

var o7 = (function(o6) {

return ((function() {

pp(str("halted with result: ", o6));

return false;

}))();

});

return o8(define_variable("\uFDD1initial", "\uFDD1foo", o10));

}))());

Note that there's not a single function statement for a continuation except the top-level ones. A neat side-effect is that we don't have to thunkify code to return it to the trampoline. We simply return the name of a function and any arguments. The top-level functions are basically labels.

Environments are lexically bound at compile-time, but you'll notice that all the environment functions simply take a string, not an actual environment. This is because I can't determine the names of the arguments when calling a function, which forces me to extend environments in the called function, but it doesn't have access to the parent's environment anymore. The runtime keeps a dict of environments and links them together based on name.

There's a few bugs (notably with the continuation stack), but it works so we can benchmark it.

Results & Performance of New CPS

What do you think? Will this new form be more or less optimal than the one in this post We had to introduce several new operations, so at this point I really wasn't sure.

My first attempt at benchmarking showed the same performance as before, which was basically it's slow as crap compared to the normal code. I was skeptical of this benchmark though because the original program is so simple that js engines can probably eat it a million times over in their sleep.

Let's add something to the test to see how each program would perform in the real world. I voted for a canvas rendering. These lines of code were added:

// setup

var canvas = document.getElementById('canvas');

var ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

// test

... loop ...

ctx.fillRect(0, 0, 450, 450);

... end loop ...

Adding in a constant slowdown to each test will show the real performance hit that we get by adding CPS instead of focusing on minute differences of performance with function allocation and other stuff.

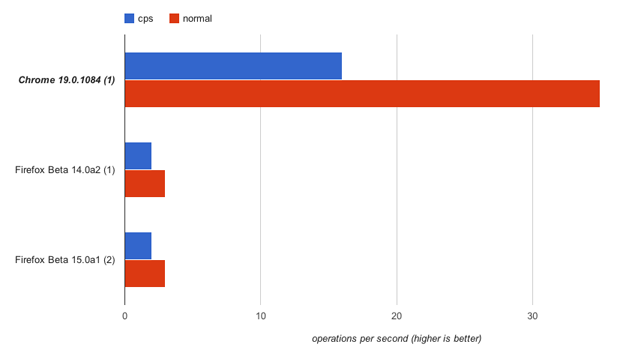

Wow, look, it's only about a 25-50% performance hit now!

Chrome performs better because of their generational GC, which is coming to Firefox in the near future. This helps benchmarks the most though, not real world code.

The huge difference between this and my last test where CPS seemed to completely kill performance, reminds me of bechmarking 3d graphics. You can easily get 7,000 frames/second if you are rendering a bunch of flat polygons, but it will drop to 900 if you add textures. It's a common mistake to think that textures incur a 90% performance hit, but in reality your computations are so trivial that you're basically benchmarking how long it takes to transfer data to the GPU. You need to strain the program more to get any real results.

The Circle of Life

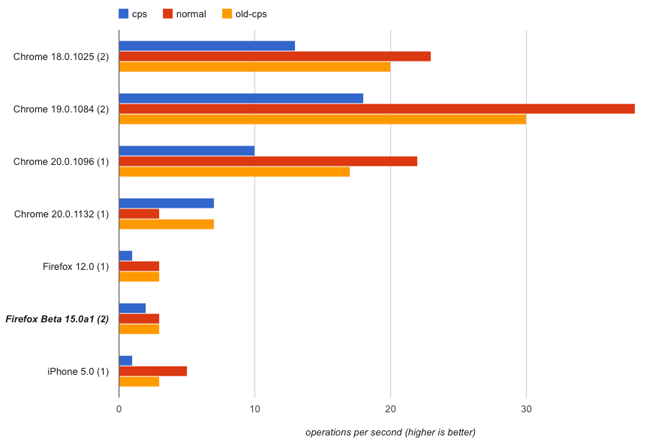

But wait a second. If the previous tests were bogus, we need to test our previous CPS form again and compare it to these results. I compiled the same program with the old CPS transform (a more traditional style), and -- wahlah! -- our previous CPS transform worked fine. In fact, it's much faster than my new attempt.

"old-cps" is my previous implementation described in this post, which is a basic transform described in Christian Queinnec's Lisp In Small Pieces. It's interesting that in Firefox there doesn't even seem to be a performance hit, but I bet it will show up in larger programs.

Result: I'm claiming this experiment as a success with a ~15% performance hit on average. We can still do better with a different CPS form, and if you don't care about fine-grained stepping you can optimize it even further.

Putting Them to Good Use

Let's play around with continuations some.

Debugger

We have everything we need to write a debugger. I implemented some hooks in the trampoline so that we can turn on and off stepping. Here's a simple program which renders boxes randomly to the screen. Note where we set a breakpoint with the debug form:

(disable-breakpoints)

(define width 400)

(define height 300)

(define ctx #f)

(define looped #f)

(define (render-clear)

(set! ctx.fillStyle "black")

(ctx.fillRect 0 0 width height))

(define (render-box color x y width height)

(set! ctx.fillStyle color)

;; SET A BREAKPOINT HERE

(debug

(ctx.fillRect x y width height)))

(define (start-box-render)

(define i 0)

(define (rand-int)

(* (Math.random) 150))

(define (rand-color)

(str "rgb("

(Math.floor (rand-int)) ","

(Math.floor (rand-int)) ","

(Math.floor (rand-int)) ")"))

(define (render-rand x y width height)

(render-box (rand-color) x y width height))

(define (render)

(if (< i 200)

(begin

(render-rand (rand-int)

(rand-int)

(rand-int)

(rand-int))

(set! i (+ i 1)))

(begin

(render-clear)

(set! i 0)))

(if looped

(begin

(set! timer (setTimeout (callback () (render)) 0)))

(render-clear)))

(set! looped #t)

(render))

(define (stop-box-render)

(set! looped #f))

(document.addEventListener

"DOMContentLoaded"

(callback ()

(let ((canvas (document.getElementById "canvas")))

(set! canvas.width width)

(set! canvas.height height)

(set! ctx (canvas.getContext "2d"))

(set! ctx.fillStyle "black")

(ctx.fillRect 0 0 width height))))

(set! window.start_box_render (callback () (start-box-render)))

(set! window.stop_box_render (callback () (stop-box-render)))

You can see it here. Hit "start" to run it, and "enable breakpoints" to make it stop on the breakpoint. "continue" resumes the program, and "step" walks through each expression.

expr:

It won't be hard to track the environment so that we can eventually inspect variables, change them, etc.

The biggest problem with CPS is inter-operability with non-CPS functions (other js libraries, native functions, etc.). You'll notice that I had to introduce the callback form in this program to create native js callbacks. This can be simplified by differentiating native calls like Clojure does with something like a dot. Callbacks passed to these functions could automatically be converted into non-CPS calls.

Continuations <3 Asynchronous (Event Loops)

Now that I've started to write "Javascript" with continuations, it turns out that using them with event loops is really fun and interesting.

It's really easy to write async code in an iterative style. I quickly wrote up the tilda (~) operator which automatically converts an async call into a simple expression. Say we have the following node.js program:

var redis = require('redis');

var client = redis.createClient();

client.set('foo', 'bar');

client.set('bar', 'biz');

client.set('biz', 'hallo!');

client.get('foo', function(err, reply) {

console.log(reply);

client.get(reply, function(err, reply) {

console.log(reply);

client.get(reply, function(err, reply) {

console.log(reply);

client.end();

});

});

});

See the callback hell? (Or, my favorite expression, "pyramid of doom") Look how easy it is now:

(require (redis "redis"))

(define client (redis.createClient))

(client.set "foo" "bar")

(client.set "bar" "biz")

(client.set "biz" "hallo!")

(let ((msg (~ client.get

(~ client.get

(~ client.get "foo")))))

(console.log msg))

(client.end)

;; output:

"hallo!"

IcedCoffeeScript uses CPS in a similar fashion, but it's much more limited and you have to deal with weird await and defer keywords. I don't think you can pause the program across function calls either, where you can here.

Note: The ~ operator ignores the error results right now, but it could be propagated up just as easily. This was a quick hack to show off what we can do.

Conclusion

The result of all of this is that I feel like I've hit a gold mine. Continuations are a really interesting technique which solves a lot of problems, especially when writing source-to-source compilers and you don't have access to the low-level internals of the target language. The possibilities are huge when you incorporate CPS.

I'm not sure how deep I will employ CPS. As I showed with the node.js example, there are very interesting applications for using it even in production code. For now, I will use it for debugging, but I may explore other possibilities as well.

All of this work is happening on the cps1 branch in Outlet. Pleaase note that my current implementation is largely a prototype and I am going to research better CPS forms. There are various difficulties with how it currently works so it will mostly be rewritten.

Follow my blog or me on twitter if you want to see where I take this.

JAMES LONG

JAMES LONG